We may genuinely, continually try our best to be compassionate, caring for everyone around us, yet the very people we cared for may often throw stones, so to speak.

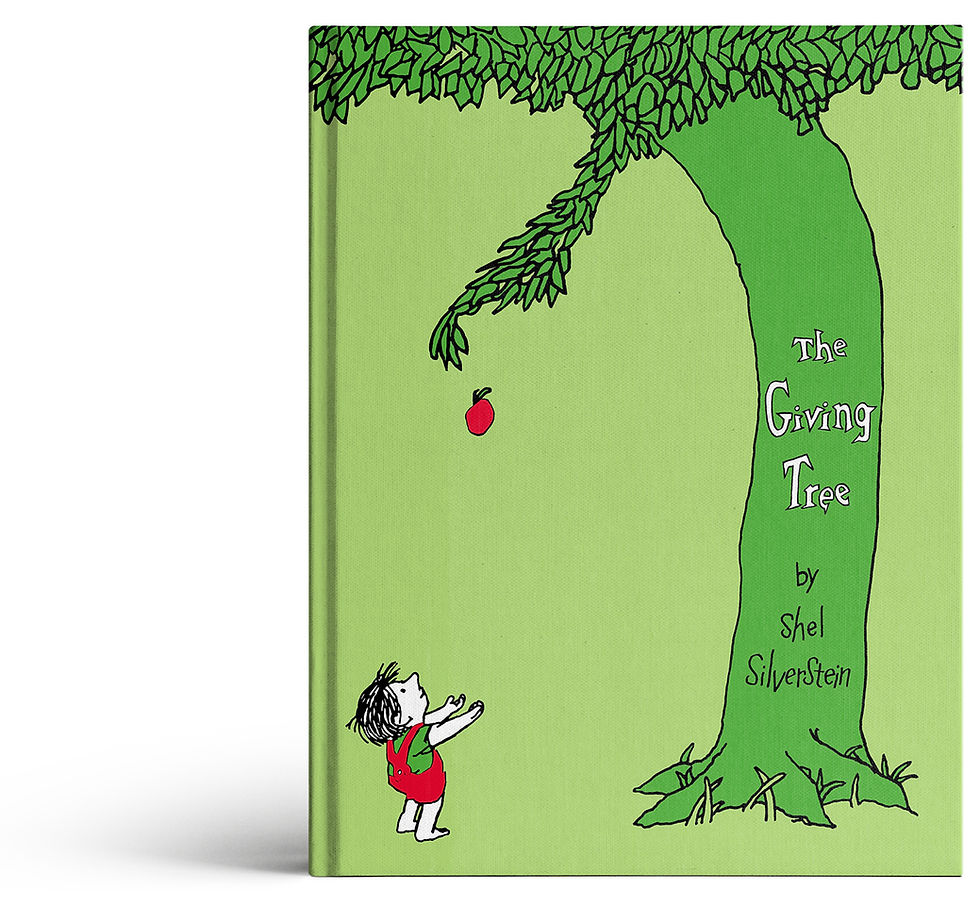

Children’s stories interest me, as they both reflect our present society and shape our future society. One of the better short stories I have come across recently is called The Giving Tree, written and illustrated by Shel Silverstein, published in 1964 and later translated into numerous languages. It is a story about a tree and a boy. It resonated with me personally because I remember that, in my younger years, there was a pomelo tree, hanging its fruit-laden branches above a dirt path. Pomelo is a citrus fruit, and it grows to be as big as a basketball. I used to throw stones at the tree in my effort to drop some pomelos to eat. In life, a lot of us are truly similar to this fruit tree, and to the tree in The Giving Tree. We may genuinely, continually try our best to be compassionate, caring for everyone around us, yet the very people we cared for may often throw stones, so to speak. When this happens, we should not be discouraged, but continue to be mindful.

We must cultivate compassion because of understanding its innate virtue – not for any other reasons. We may fail at times to remember why we are cultivating loving-kindness and compassion. For some individuals or groups of people, we may end up not having very compassionate thoughts, simply because their reactive feedback to our compassionate gesture was not up to our standards. After such instances, we may then closely conceal our compassion like a precious jewel, exposing it only to a chosen few worthy ones. Receiving the expected responses from them, this sense that we have been successfully compassionate can then sometimes become a reason to feel superior over others. The compassion, or rather, this feel-good factor we perpetuate, is just like any other feel-good factor we have in life – there is nothing compassionate in it.

When we started following the principle of compassion, we chose to do so, because of not being able to imagine ourselves operating in any other way. This is the way.

We knew then, and we can know now, that our development of compassion for sentient beings was not contingent on what we may receive in return, but rather, that we practice compassion for its own innate virtue. We chose compassionate action over non-compassionate action, because that is the way of life we saw fit for ourselves. Though it may have had a thoughtful inception, such compassion, however, when not paired with the wisdom of mindfulness, frequently leads us to either discouragement, or becomes a way to feel good about ourselves, which was never the intended goal of compassion when we started the practice. Therefore, just like a training gymnast has to balance on the beam consistently, similarly, we must always be mindful of the very reason for being compassionate and kind. Determined to perpetuate the best version of ourselves, when we feel that we are being hit by stones, we must carry on being who we always wish to be. Remembering why we are practicing compassion enables us to remain in the practice.

On the other hand, occasionally, upon failing to be the best of ourselves, we may be lightly mocked by our friends and relatives, commenting on how our behavior was not up to par with Buddhist principles. We should, again, introspectively think, along the lines of what Sakya Pandita said in Ordinary Wisdom, and I paraphrase: People examine faults in the excellent ones only, just as they examine precious material such as gold and diamonds. This is true. Those in the path of excellence are scrutinized. Diamonds are coveted, but have we heard of anyone coveting ordinary rock? No. With that reason in mind, we must remember that, while we are on the path, if our unmindful behavior sometimes becomes a subject of discussion, we can infer that this scrutiny, and our initial tendency to fall short of more perfect aspirations, are part of this path. Thus, not discouraged, we must carry on in the path of mindfulness and compassion, determining to be the best we can be, performing all the social roles we have, such as parents, children, spouses, sibling, peers, friends, and above all, being a mindfully compassionate human being.

Decades have passed, and I am long gone and grown, but the pomelo tree I used to throw stones at still does what it always does the best – bear fruit and give shade. This is how nature works, and so should we – stones or boulders, we maintain who we are. To some pragmatics, this may be lunacy, but for compassion practitioners, this is considered to be the path of bodhisattvas, and we are a sangha of bodhisattvas, steadfastly renewing our vow with every stone that is thrown.